Scientists develop new approach to support future climate projections

Descent into the Icehouse members Gavin Foster and Dan Lunt, as part of the multinational Palaeosens project lead by Professor Eelco Rohling, have re-evaluated published estimates of prehistoric climate sensitivity. The results of this are published in Nature today. This is the press release that can also be found on the University of Southampton’s website

Scientists develop new approach to support future climate projections

Scientists have developed a new approach for evaluating past climate sensitivity data to help improve comparison with estimates of long-term climate projections developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The sensitivity of global temperature to changes in the Earth’s radiation balance (climate sensitivity) is a key parameter for understanding past natural climate changes as well as potential future climate change.

Many palaeoclimate studies have measured natural climate changes to calculate climate sensitivity, but a lack of consistent methodologies produced a wide range of estimates as to the exact value of climate sensitivity, which hindered results.

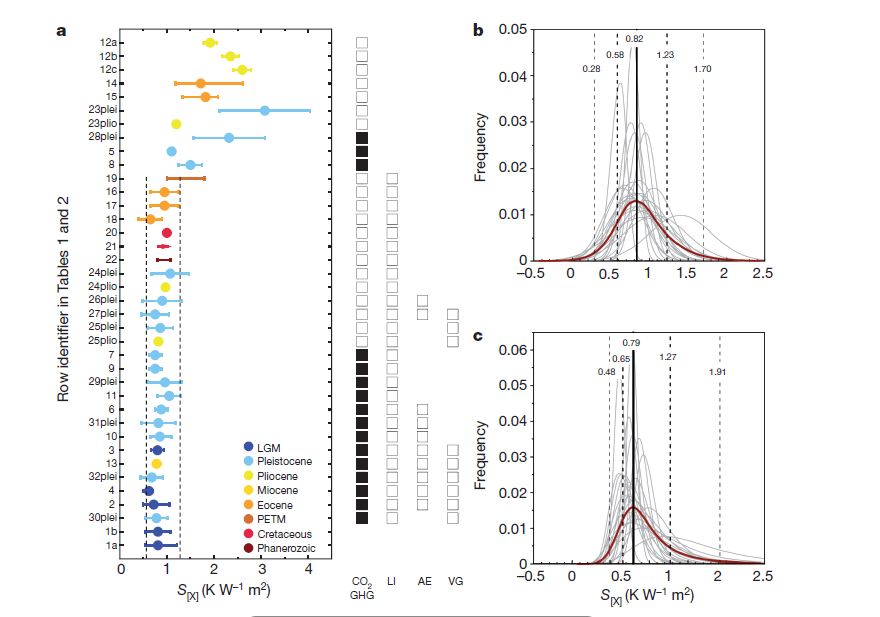

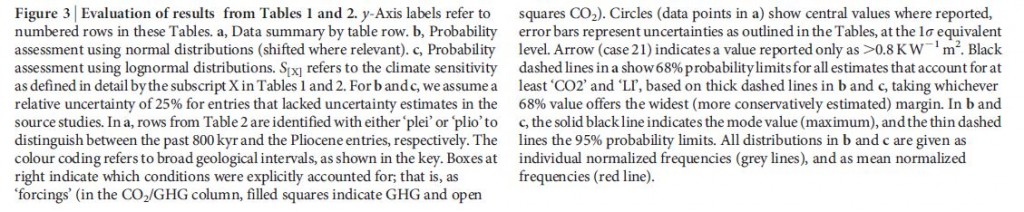

Now a team of international scientists, including Eelco Rohling, Professor of Ocean and Climate Change at the University of Southampton, have developed a more consistent definition of climate sensitivity in prehistoric times. When the scientists evaluated previously published estimates for climate sensitivity from a variety of geological episodes over the past 65 million years, they found that the estimates varied over a very wide range of values, with some very high values among them (high values would imply a very strong temperature response to a change in radiative forcing, for example, due to CO2 increase).

The team discovered that this wide range was almost entirely due to the fact that different researchers used different definitions. Similar to biologists needing taxonomy to ensure that they all talk about the same organisms, the scientists needed to develop a definition terminology that, applied to estimates from the past, makes those estimates compatible with estimates from climate models as used by the IPCC.

Professor Rohling, who is currently based at the National Oceanography Centre Southampton but will join the Australian National University next year, says: “Consistent intercomparison is a top priority, because it is central to using past climate sensitivity estimates in assessing the credibility of future climate projections.

“Once we had developed the framework and we had elaborated all the different assumptions and uncertainties as well, we applied it to climate reconstruction data from the last 65 million years. This caused a much narrower range of estimates, and this range was now defined in such a way that we could directly compare it with estimates in the IPCC assessment for their longer-term (several centuries) outlook.”

The scientists found that the likely range of climate sensitivity consistently has been of the order of -2.2 to 4.8 degrees C per doubling of CO2, which closely agrees with the IPCC estimates. Currently, atmospheric CO2 levels are around 392 parts per million (increasing by about 2.5 ppmv per year). Pre-industrial values were around 280 ppm, so that a doubling would therefore imply 560 ppm (at the current rate of emissions increase, this would achieve a doubling roughly around 50 to 70 years from now, but this depends strongly on the emissions developments).

Professor Rohling adds: “Our study only documents what the climate sensitivity has been over the last 65 million years, and how realistic the estimates of the IPCC are in that context. It finds that those estimates are fully coherent with what nature has done in the (natural) past before human-based effects. Hence, it strongly endorses the IPCC’s long-term climate projections based on such values: nature shows us it always has, and so likely will again, respond in a way close to what the models suggest, as far as warming is concerned.”

The research stems from a three-day Academy Colloquium attended by about 40 internationally renowned specialists in past and present climate studies, held at the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in Amsterdam last year.

The findings are published in the latest edition of the journal Nature.

Notes to editors:

- A copy of the paper ‘Making sense of palaeoclimate sensitivity’ is available from Media Relations on request.

- The University of Southampton is celebrating its 60th anniversary during 2012.

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, granted the Royal Charter that enabled the University of Southampton to award its own degrees in the early weeks of her reign in 1952

In the six decades to follow, Southampton has risen to become one of the leading universities in the UK with a global reputation for innovation through academic excellence and world-leading research.

This year, the University’s reputation continues to grow with the recent awarding of a Queen’s Anniversary Prize for Higher and Further Education in recognition of Southampton’s long-standing expertise in performance sports engineering. To find out more visit www.southampton.ac.uk/60

3. The National Oceanography Centre (NOC) works in partnership with the UK marine research community to deliver integrated marine science and technology from the coast to the deep ocean.

It was formed in April 2010 by bringing together the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC)-owned Proudman Oceanographic Laboratory in Liverpool and NERC-managed activity at the National Oceanography Centre, Southampton into a single institution.

With its partners, the NOC delivers the research capability needed to tackle the big environmental issues facing our planet. Research priorities include the oceans’ role in climate, sea level change and the future of the Arctic Ocean.

The University of Southampton and the University of Liverpool are hosting partners of NOC. Ocean and Earth Science at the University of Southampton shares a waterfront campus with the NERC-operated elements of the NOC, and a close collaborative relationship is maintained at both Southampton and Liverpool.

For further information contact:

Glenn Harris, Media Relations, University of Southampton, Tel: 023 8059 3212 email: [email protected]

Links

Follow us on Twitter

Recent Posts

- In the News : What a three-million year fossil record tells us about climate sensitivity

- Past evidence confirms recent IPCC estimates of climate sensitivity

- Crucial new information about how the ice ages came about : PR & Podcast

- 2014 Sino-UK Coevolution of Life and the Planet Summer School

- Past and Future CO2 – Reconstructing atmospheric Carbon Dioxide